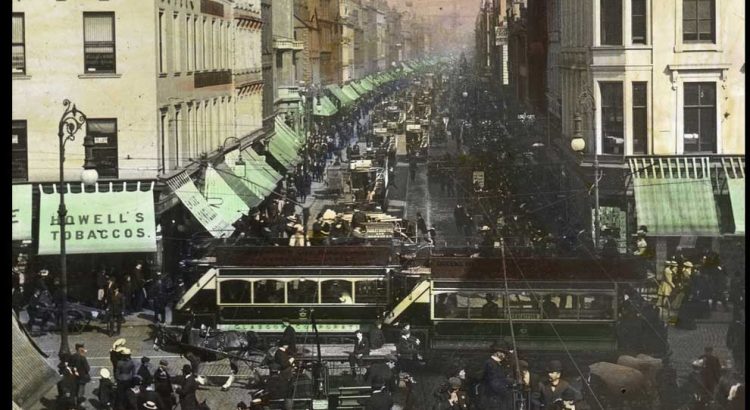

Glasgow

I was born in Glasgow in 1957. I haven’t lived there since 1980 but some of my books describe the city. Most of the action in The Figure in the Photograph, an Edwardian thriller, takes place in a district south of the River Clyde once notorious for poverty and violence; the heroine of My Father’s Revolutionary Shoes, a World War One adventure story, is a music teacher from Glasgow; and Out of the West has long sections set in Glasgow in the 1940s.

My first job after graduation was at the British Institute in Florence. The Games, a spy thriller set during the 1960 Rome Olympics, explores some picaresque corners of Italian life. I worked briefly at the Citizens’ Theatre in Glasgow, and then spent 14 years in Asia.

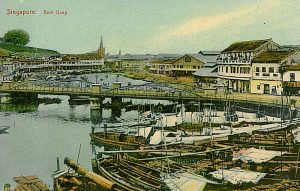

Singapore

In Singapore I crashed my motorbike, worked as a restaurant reviewer and an art critic, wrote several novels, was criticised in Parliament, and came to love the scent of jasmine and the sound of mahjong tiles through open windows on tropical evenings. My comic novel, Trouble in the Tropics, examines how citizens strive to maintain their integrity in an authoritarian state.

Japan

I moved to Japan in 1985 and worked for a year at The Japan Times, before becoming a correspondent for a business magazine. In 1989, after I had spent time in China covering the pro-democracy movement’s catastrophic demise at Tiananmen Square for the Glasgow Herald, I became the Guardian’s Japan correspondent. During a visit to Tokyo, Boris Yeltsin told me not to provoke him. We were both drinking at the time. I put my Japanese experience into The Assassin’s Footsteps, a thriller about a plot to assassinate Mrs Thatcher at the 1986 Tokyo G-7 Summit.

Bosnia

In 1992 I moved back to Singapore and then after several months to Bosnia. I had spent some time in Dubrovnik at the beginning of the siege in 1991, and regretted returning to Japan to cover a change of government.

A friend took my RAF flying jacket (indispensable for motorbike riding during Tokyo winters) out of storage and sent it to Singapore just in time to take to Bosnia. On my balcony in Singapore I tried it on and took it off again after 30 seconds. It was impossible to wear in the tropical heat. In Sarajevo it was a lifesaver. When I drove over a landmine at the end of January 1993, I lay on a rubble strewn street a metre from another unexploded mine amid the sound of small arms fire – and the thing that preoccupied me was that the sleeve of my flying jacket had been torn. The mind plays tricks. It was an excellent jacket.

In Sarajevo during the winter of 1992 I met people whose homes had been destroyed and whose family members had been murdered – and their response to what was happening was very often characterised by dignity, compassion and fortitude. I hope that a fraction of this is reflected in The Longest Winter.

The day I arrived in Sarajevo I met my wife. Marija was in the lobby of the UN headquarters waiting to do an interview for the daily newspaper, Oslobodjenje. Our first date was a visit to the paper. I took a wrong turning and got shot at as I stumbled across torn-up tramlines. I survived. Marija was waiting at the front door. Romance followed.

Up and down stairs

When I was wounded, I was evacuated by the RAF (none of the C130 crew wore flying jackets like mine, which was a great disappointment). Marija arrived in the UK two months later, a few days after I was discharged from hospital, and we travelled back to Sarajevo together. In the following months I wrote the first draft of The Longest Winter in a very cold room in the western suburbs. Every day I practised walking up and down the stairs of the apartment block.

Spain

We lived in Singapore for three years after leaving Bosnia, and then we settled in Spain for five years. During our Spanish interlude our daughter Katarina was born. We wrote more books.

Sarajevo

In 2001 I was hired as a speechwriter and spokesperson for the international official responsible for implementing the civilian provisions of the Dayton Peace Agreement. I found the world of diplomacy disconcerting. There are earnest and protracted arguments over the precise wording of individual phrases in policy documents. These arguments are conducted in bare rooms with low ceilings, bright lights, large tables and a multiplicity of suits. I am glad, though, that I had a chance to make a small contribution to helping Bosnia and Herzegovina recover from the war.

At the end of 2006 I went back to writing novels. We divided our time between Spain and Sarajevo and among other things I completed In the Company of Phantoms, a thriller set in New York, and The Field at Friedland, an adventure story set in East Prussia in 1904.

In 2014 I joined the International Commission on Missing Persons. Founded in 1996 to help account for the 40,000 people missing at the end of the conflict in former Yugoslavia, ICMP spearheaded the innovative use of mass DNA database technology through which it has been possible to identify more than 70 percent of the missing, including more than 90 percent of the 8,000 victims of the 1995 Srebrenica Genocide. It now works all over the world.